#31: Five for Them, One for Me, with Nick Kolakowski

Nick’s latest, WHERE THE BONES LIE, is out Tuesday, March 11.

From slasher horror (GROUNDHOG SLAY) to 60s-style crime (PAYBACK IS FOREVER) to a post-apocalyptic heist (MAXINE UNLEASHES DOOMSDAY), Nick Kolakowski is a writer always ready to subvert expectations. His ability to upend storytelling conventions may mean the book of his you finish is a complete 180-degree turn from the one you started, but there’s also a guarantee you’ll have a good time along the way.

His latest, WHERE THE BONES LIE, brings Nick’s customary twisty plotting and narrative propulsion to the California PI novel. The book centers on Dash Fuller, a former Hollywood fixer who becomes involved in the murder investigation of a long-lost smuggler whose body is discovered in a barrel at the bottom of a dried-up lake. Dash ends up ensnared in a tangled web of lies and conspiracies—it is a California PI novel, after all—that builds toward a fiery climax. It’s an exciting read, and solidifies Nick as one of the most entertaining writers in crime fiction.

Nick’s also the latest Five for Them, One for Me.

Let’s go.

FIVE FOR THEM

1. Talk to us about the origin point for WHERE THE BONES LIE.

I’d always wanted to write a “traditional” detective novel, but I’d never been able to find a hook that worked for me. I’m not smart enough to write one of those genius puzzle-box narratives where the impossibly erudite detective determines the killer thanks to their esoteric knowledge of accents (or something along those lines), and I don’t have the background (or research time, frankly) to effectively pull off an effective, realistic cop or espionage thriller. There are so many great detective novels, you really have to sit and ask yourself: “What am I doing that’s unique? Why would a reader choose what I’m doing over, say, re-reading Michael Connelly or John le Carré?”

For me, the answer was pretty straightforward: I would pull something from my own experience. My background as a journalist meant I had insights into a couple of interesting worlds: cigars (I ran a cigar magazine at one point), tech (I’ve worked as a tech journalist for a few big publications), and Hollywood (from being a celebrity interviewer/luxury magazine editor). For a couple of reasons, I opted to take the Hollywood route. If I get the chance to write a sequel to “Where the Bones Lie,” it’s going to involve a lot of tech and Silicon Valley, which in many ways is just as seedy as anything in L.A.

2. I’ve been a big fan of your work since BOISE LONG-PIG HUNTING CLUB—a book that absolutely cooks, BTW—and what I notice is how you’re willing to take big creative swings most of us would never consider. How do you balance that level of experimentation alongside all of your other storytelling considerations?

I get bored to tears incredibly easily. That’s one reason why my books tend to have a speedy pace—they’re a reflection of my own attention span. That fear of boredom also leads me to experiment with form. For example, when I wrote “Rattlesnake Rodeo,” the second in my series of books about an Idaho bounty hunter and his gun-running sister, I tried writing the climatic gun-battle in all sorts of ways, but it came off as a retread of a million other literary firefights. Fortunately, I was also really into the novels of Hungarian writer Laszlo Krasznahorkai at the time, and I decided his prose style—incredibly long sentences that sometimes stretch for page after page, generating this sense of unstoppable momentum—was the answer to my issue. As a result, the last battle of “Rodeo” suddenly shifts crazily into this unexpected stylistic gear, pushing the characters along through fire and death, with sentences designed to be as breathless as possible.

I didn’t go nearly that nuts with anything in “Where the Bones Lie,” but I did infuse parts of it with elements from other genres—there’s the faintest touch of cosmic horror in there, which hopefully plays a bit like an outtake from “True Detective,” and a heavier dose of John Carpenter-style masked stalking. But whatever I’m toying with, my primary concern is that the narrative moves; if someone’s plunking down their money and a few precious hours of their life for my book, I’m going to do my best to give them the best time I can.

3. You’re a New Yorker, but you set WHERE THE BONES LIE in L.A. What led to this decision, and what were the challenges you faced to make sure you got L.A. and California right?

I spent a significant portion of my twenties as a journalist for a bunch of newspapers and glossy magazines, the kind that have celebrities on the cover. That job plunked me in L.A. and Vegas for sizable portions of time, and it gave me an angle on the weird beast of Hollywood—not just the actors and musicians and directors I was interviewing, but also the PR folk and personal assistants and everyone else feeding the beast from below. It resulted in a sort of whiplash: I got to participate in cool stuff—having a famous late-night host take you aloft in their Cessna or an NFL superstar joyride with you at insane speeds isn’t for the faint of heart—but I also witnessed some disquieting, weird behavior. It eats at you after a couple of years.

Obviously, that’s a very different background than writers who live in that L.A. milieu full-time, and I was careful to stay within the guardrails of what I’ve personally experienced. For example, in the book, Dash and Madeline start in L.A. and then drive up the coast to the fictional town of San Douglas, where much of the action takes place—that’s based closely on my trips up to Santa Ynez. Characters like Manny, the fixer who was Dash’s boss in a former life, are aggregations of people I’ve known. Many of the stories that characters tell each other are based on things I heard secondhand.

I still go out to California fairly regularly; I have family in Long Beach, and up until last year I was shuffled off to San Francisco and Silicon Valley and Napa and other points on a distressingly frequent basis for work. I did my best to get California and L.A. right, but I was also trying to create a fictional world, a sense of the American Dream on fire. I probably got some things wrong. I hope I got most of it right.

4. Several early chapters of WHERE THE BONES LIE were also a Derringer-nominated short story titled “Back to Hell House,” published in Vautrin back in 2023. Did the short story or the novel come first? In what ways did the different forms feed into one another?

The short story came first. Every novel or novella I’ve ever written has started as a short story. When I finish working on a story, sometimes I’ll feel a tickle in the back of my head that suggests that particular narrative has a little more to it—that’s how I ended up writing “Boise Longpig Hunting Club” and a few other books.

With “Where the Bones Lie,” the short story (which ended up titled “Back to Hell House”) also operated as something of a test bed, since I hadn’t really written detective fiction before. I wanted to get a handle on a shorter, sharper detective-story arc before exploding it out to a full-size novel. Working on the short story was useful on that front, as well, although I also discovered that a detective novel involves so many other factors that don’t appear quite as often in a shorter tale, considering their respective lengths—red herrings, twists that take several hundred pages to build up, etc. It’s been an educational experience, to put it mildly. Writing “Where the Bones Lie” took probably twice as long as my typical book.

5. You’ve talked about reading EVERYBODY KNOWS by Jordan Harper while writing this book and how several themes overlapped with WHERE THE BONES LIE. That said, they’re different books the same way ARMAGEDDON and DEEP IMPACT are different movies about a meteor. Did you have any trepidations about finishing WHERE THE BONES LIE? What were some of the choices you made to be sure this was a distinctly Nick Kolakowski jam?

I started writing “Where the Bones Lie” around four months before “Everybody Knows” came out. I knew Jordan’s book involved Hollywood fixers in some capacity, but I had no idea he was crafting a noir masterpiece. When “Everybody Knows” finally dropped, I read it in a weekend—and promptly had a major psychological crisis.

The crisis went something like this: “Everybody Knows” is a tour de force of plotting, pacing, characterization, and wordsmithing. It was a solid contender for my favorite mystery novel of 2023—and it’s maybe the best mystery novel of the decade. To my great relief, the plot of “Where the Bones Lie” was wildly different from “Everybody Knows,” but Jordan’s description of the Hollywood underbelly was so nuanced, evocative, and real that it stopped me dead in my tracks, writing-wise. How do you even begin to compete with something like that?

The weekend after I finished “Everybody Knows,” I was reading at Noir at the Bar at Shade, a watering hole in NYC. I had chosen a bit from “Groundhog Slay,” my horror-comedy novella where a masked, Jason Vorhees-style killer finds himself stuck in a time loop. As I was introducing the piece, I mentioned that I was trying to work on a California detective novel that had stalled out after I’d read Jordan’s book, and I wasn’t sure whether I’d get back to it.

Todd Robinson, who works at Shade and is widely considered the godfather of NYC’s crime writer scene, thanks to his peerless editorship of Thuglit (a magazine where many of us got our real start), wasn’t hearing any of that. When I finished, he marched up—and given his size and muscle mass, when Todd marches up on you, it’s an overpowering event, like a tsunami—and yelled, “JORDAN IS DOING HIS THING, YOU ARE DOING YOUR THING, YOUR THING IS GREAT, JUST DO YOUR THING.”

I’m paraphrasing there, but Todd’s force really knocked loose the block in my head. I wasn’t concerned about plot or character overlap between “Where the Bones Lie” and “Everybody Knows,” so I didn’t need to tweak anything on that front. I just had to wrestle with the idea that any modern-day California noir narrative must exist in the shadow of everything Jordan’s doing. It took another nine months of writing for me to finish the book, but it got done.

ONE FOR ME

Your work often blends genres, mixing a heist story with a techno-thriller, slashers with science fiction, or cons on the run with conspiracy theories. What’s the wildest cross-genre swing you’ve thought about but haven’t gotten to take yet?

Oh, it’s definitely historical fiction. Several years ago, I had the idea for a novel that combined 19th century Arctic exploration with a serial killer narrative with a bit of time travel, and I even did a lot of the necessary research, but I couldn’t get the flow or the dialogue right—whatever came out of the characters’ mouths was too alien, their behavior too stiff. I’ve always wanted to take another run at something like that, if only to justify my college degree in U.S. history. Maybe a werewolf tale in the Old West? Aliens in Victorian England? I’ll do it one day!

RIP, JOSEPH WAMBAUGH

Joseph Wambaugh, the former L.A. cop who funneled his 14 years of experience on the beat into a second career as a best-selling novelist and screenwriter, passed away last week at the age of 88. His best-known works were probably his initial run of novels from the early 1970s into the mid-80s, including THE NEW CENTURIONS (1971) and THE CHOIRBOYS (1975), as well as his non-fiction book THE ONION FIELD (1973). He also co-created the Emmy-winning anthology series POLICE STORY, which ran from 1973-1978.

I picked Wambaugh up later in his career, starting with THE GOLDEN ORANGE, probably not long after it came out in 1990. I’d already been reading Ed McBain’s 87th Precinct novels for four or five years, and had a naive sense of the rhythm of police work and the camaraderie of cops. What I saw in Wambaugh’s work, though, was less about the technique and more about how the job wore the characters down. As Wambaugh said, “I concentrated not so much on how the cop acts on the job, but how the job acts on the cop.”

Looking back, it’d be easy to accuse Wambaugh of writing “copaganda,” but it’s not that simple. Wambaugh’s cops were messy and complicated, damaged by what they’d seen on the job and the (poor) choices they’d made to cope with the aftermaths. He portrayed a system broken by power and money and corruption. Along the way he added layers of satire, having fun with California excess. His influence is certainly felt in the writers who came after him, including Michael Connelly and Robert Crais.

SHAMELESS SHILLING

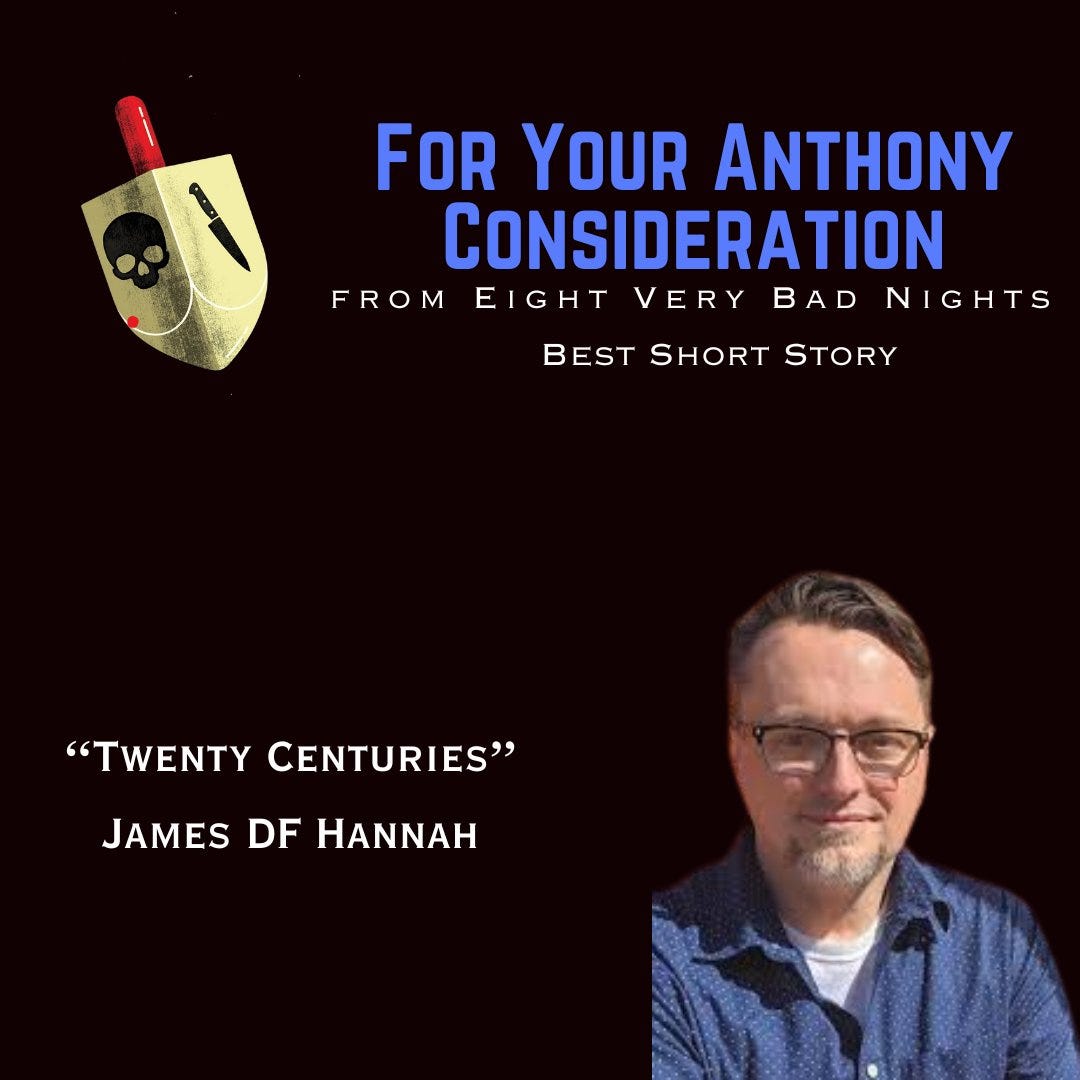

My story "Twenty Centuries” was chosen for The Mystery Hour podcast and given a fantastic reading by Rabia Chaudry. And please hang around after the story ends as Ms. Chaudry discusses the story's real-life parallels.

If you’ve been read this newsletter for long, you know the story features Sheriff Charlotte "Crash" Landing from my Henry Malone novels. It was originally published in the November/December 2024 issue of ELLERY QUEEN MYSTERY MAGAZINE as well as EIGHT VERY BAD NIGHTS, edited by Tod Goldberg.

The story is now free on my website, if you’ve somehow missed out reading it before now.

Anthony nomination ballots have gone out to planned attendees for Bouchercon 2025, scheduled for September 3-7 in New Orleans. If you’re got a ballot and you enjoyed “Twenty Centuries,” I hope you’ll consider nominating it for Best Short Story.

If you’re looking to fill out your Best Anthology nominations, you can’t go wrong with EIGHT VERY BAD NIGHTS. It’s a great collection of stories from an absolute top tier of crime writers—and also, me. I mean, would Oprah Daily or the Jewish Book Council steer you wrong?

That’s all we’ve got for now. Thanks for coming. See you next time, and hey, let’s be careful out there.

Great interview, James!