#34: Five for Them, One for Me, with C.W. Blackwell

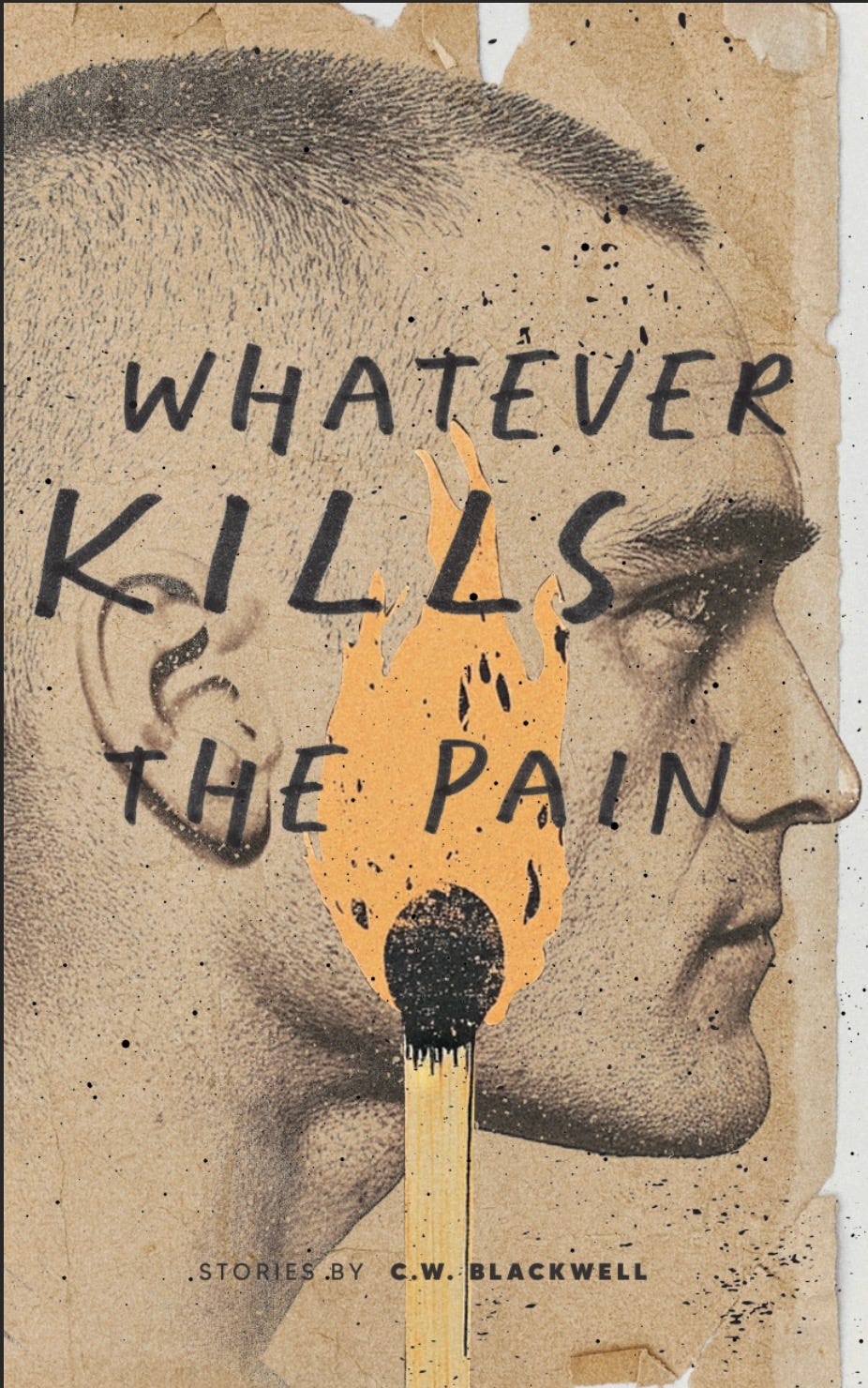

C.W.'s latest, WHATEVER KILLS THE PAIN, is out July 18. It's available for pre-order now.

C.W. Blackwell has steadily built an impressive reputation as one of the finest short story writers in crime fiction in recent years—and with good reason. His work pulses with an immediacy and a vitality that takes familiar crime fiction scenarios—a heist goes wrong, a financial adviser ends up working for a drug kingpin, a struggling family at conflict with their wealthy neighbors—and moves them past simple entertainment. C.W.’s stories are reflections on the class war in America, told through an appreciable genre lens. His stories will move you and shake you. They will make you angry. And they will stay with you long after you’ve turned the last page.

C.W.’s short fiction has been honored twice with the Derringer, presented by the Short Mystery Fiction Society, and he’s nominated again this year. He’s also the author of HARD MOUNTAIN CLAY and the folk horror novella SONG OF THE RED SQUIRE.

His latest is the short-story collection WHATEVER KILLS THE PAIN, out July 18 from the good folks at Rock and a Hard Place. I’m thrilled to get to do to get to do a reveal of the book’s fantastic cover—designed by Heather Garth—here at That Noise at 2 AM. I’ve read WHATEVER KILLS THE PAIN, and I can tell you already it’s one of the best collections of the year.

C.W.’s our Five for Them, One for Me.

Let’s go.

FIVE FOR THEM

1. The introduction to WHATEVER KILLS THE PAIN isn’t just an introduction; it’s an indictment of late-stage capitalism and the collapse of the middle class. The anger is palpable. What is the role of anger in your writing?

I think writers always look for a spark to get them into the seat. When it’s not there, you still have to show up—some of my best writing has come from simply sitting down and trying to move the cursor along the screen without much motivation. But if you ask a roomful of writers if they’d rather have a spark than not, you’d see a lot of hands. Grief, intrigue, fear, and love all make great sparks—and anger is just as good. Lately, anger has played a larger role in my writing. Although my stories aren’t overtly political, they are very much informed by my personal politics. I tell stories of working class people smothered by a system that mostly benefits the wealthiest families in America. The destruction of the middle class and systematic oppression of working families in this country has real life-and-death consequences. Life expectancies are dropping, college is out of reach, childcare now costs as much as rent, and behavioral health treatment isn’t often available until people are already in crisis. All this is happening while America is about to create a new trillionaire class—a distinction that might as well be a declaration of war on the working poor. It certainly makes me angry, and I know I’m not alone.

2. You tell stories set in different time periods—“Hard Rain on Beach Street” is set in 1978, the title story takes place in 1960—but the stories speak to the present day. How does writing about different time periods help you convey what you want to say about today?

Many writers fall victim to a bit of nostalgia, and I’m no different. Most of the books I love were written decades ago, so it’s easy to start a narrative in that voice, set in a distant point of time. It feels romantic. I also have a certain disdain for the present. Maybe it’s a natural part of getting older, but I’d much rather live in a world without social media, the internet, MAGA ideology, corporate coffee shops, vapid popular music, etc. But I also want to demonstrate how the social issues we face today are very old devils. The wealthy have always exploited the working class. The landowners have always exploited the renters. The old devils are always hungry, and nothing will ever satiate them. So when I set my stories in the past, I’m not just trying to scratch the itch of nostalgia, I’m demonstrating how the fight has been raging for a long time, how the one percent are very determined, and if we give an inch, it’s an inch we won’t ever get back.

3. A story that really struck me was “A Little Rain Must Fall,” about a couple who go on the run with a bag of drug money. It’s such a classic noir set-up and it harkens to the fatalism of Jim Thompson, but it feels distinctly modern. Talk about taking the classic noir tropes and bringing them to modern times.

I’m a huge Jim Thompson fan. I love how his stories go from stasis to death and destruction so effortlessly and without exposition. He simply drops you in and sends you on a ride. Another thing I respect about Thompson’s work is his lust for realism. I think his characters feel real largely because his father was both a lawman and an outlaw, and because his own experiences as a young man hustling dope at the Hotel Texas give his stories authenticity. I would never compare myself to him, but my work as a crime analyst also grounds my work in harsh realism. So when I write about a working class couple who makes off with a duffle of drug money, it’s because it can happen, or maybe has happened in my community. My day job informs my fiction in a significant way. It’s been my experience that the nihilistic outcomes of Thompson’s noir stylings are alive and well in modern day crime cases, and it’s my absolute favorite thing to write about.

4. I really loved the ambiguity of several stories in the collection—specifically the missing child story “I Keep Coming Back Empty Handed.” You’re obviously not interested in easy answers for readers. As a writer, do you worry about reader’s expectations, or are you just comfortable with the ambiguity?

I accept ambiguity as one of life’s central characteristics. It’s rare to have all the answers when tragedy strikes a community, and part of the struggle of being human is to cope with the pain of uncertainty. People are killed and no one knows why. Sometimes there aren’t any answers at all. It’s madness, but it’s true. “I Keep Coming Back Empty Handed” is also true. Not the lost child part, but Danielle’s story. The tragedy rocked our little Central Coast neighborhood thirty-five years ago and made us question everything. We still talk about it. To write about it with absolute certainty would be wrong, since we still don’t know why it happened. But the scars of the living are certain. We can count those. I don’t think a story needs to worry about all the “whys” and “how comes.” Sometimes all a story needs to do is to count the scars.

5. Even the stories that have “happy” endings begin in extremely dark places—I’m thinking “No Wrong Way to Grieve,” about school shootings and the gun industry—and the “wins” for these characters still feel like bitter pills. How do you balance a need or desire for hope amidst the darkness of your world? How much does your fictional world need to reflect the real world?

As a writer, I think it’s important to describe the act of hope. This is another defining human characteristic. We want to believe that things will get better, or that things have a chance of improving somehow, whether or not we have the strength to see it through. But I think that’s where a writer’s obligation ends. The longing is real, so we must write it. But I feel that putting a bow around it would be a disservice to both the character and the reader, and all the characters and readers that came before them. Sometimes we try to make things better and we only move the needle a tiny bit. Sometimes we make things worse. But if I do my job right, you’ll read about the act of hope and it will make you hope too, and now you’ll feel a connection to the character, who isn’t that different from a real person. Sometimes we just need a connection, any connection. And sometimes we just need to feel something real—or real enough—even if it doesn’t save the world.

ONE FOR ME

We’ve chatted a few times throughout the years, and you’re one of the nicest and friendliest folks I’ve met in the crime fiction community, even as you write this very bleak fiction. What comedies do you watch to get your mind off all the darkness?

It’s funny you say that, because I think you are also one of the nicest guys on the crime fiction scene. (Ed: Thanks, C.W. I’ll PayPal you that $20.) Unfortunately, I’ve lost my taste for pure comedies. My wife and my youngest son like sitcoms, so it’s common at my house to hear a laugh track in one room, and the foreboding score of a crime drama in another. Don’t get me wrong, I like a well-timed joke to break up the bleakness. Great crime dramas are peppered with them. But the best I can do these days is something like “Hacks” which is very funny, but also very poignant and sad at the same time.

WHAT WE’RE WATCHING

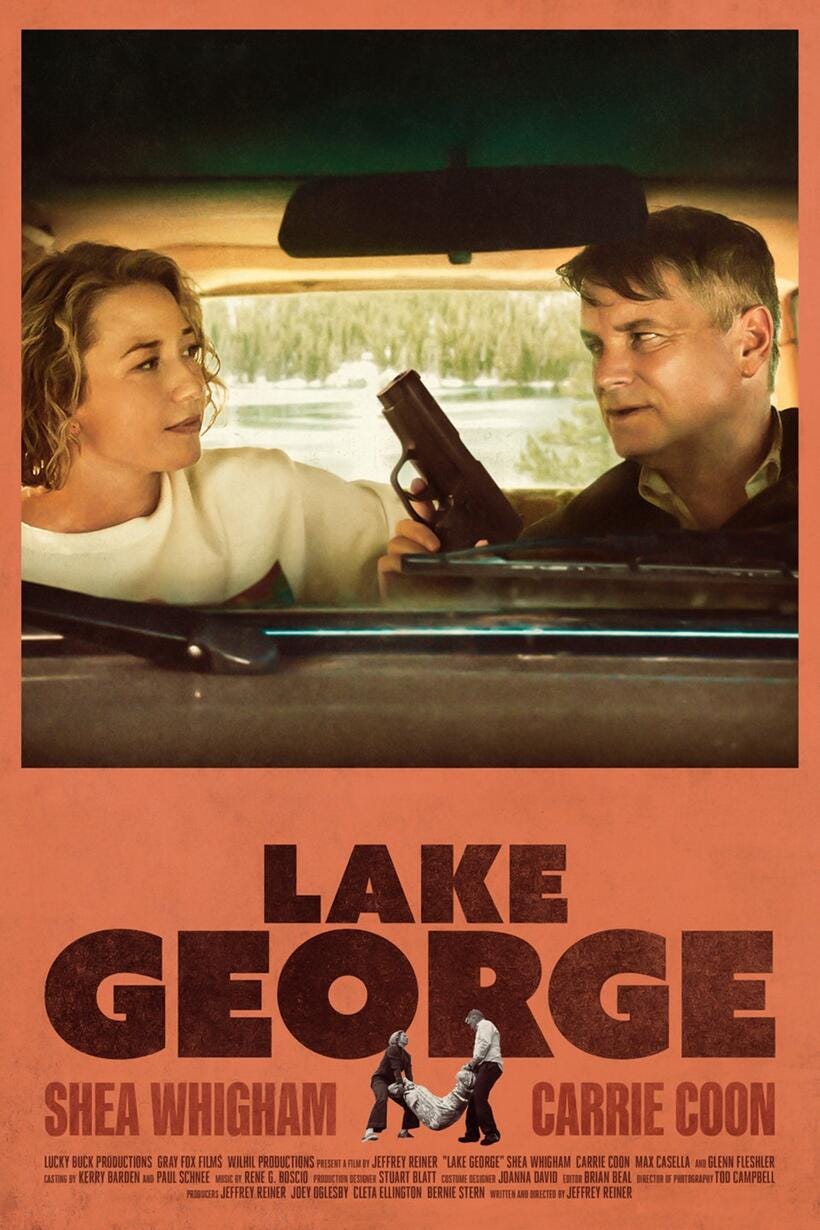

Shea Whigham and Carrie Coon are both in that rare breed of actors who improve every project just by showing up. The neo-noir LAKE GEORGE gives these two actors—normally cast in supporting roles—the spotlight in a dark-humored variation of classic films like DOUBLE INDEMNITY. Ex-con Don (Whigham) is instructed by an Armenian gangster to murder the gangster’s girlfriend, Phyllis (Coon). When Don can’t bring himself to murder, Phyllis convinces him to join her in robbing the gangster’s stash houses.

Whigham and Coon are nothing less than wonderful together, with Whigham’s exasperation contrasting to the high-energy Coon. There’s never any attempt to force a romance between the pair; instead, this is the (twisted) story of two individuals firmly in middle age, navigating one more struggle in life, and trying to find a way to come out ahead. It’s a low-key character study by turns funny and violent, with an appropriately sad and poignant ending; to paraphrase Bugs Bunny, “What’d you expect in a noir? A happy ending?”

Highly recommended.

Available on Hulu.

That’s all we’ve got for now. Thanks for coming. See you next time, and hey, let’s be careful out there.

Oh my god, that cover!!

C.W. is always always cool to read! And that collection is amazing, I was lucky to get a peek...