#43: Five for Them, One for Me, with Archer Sullivan

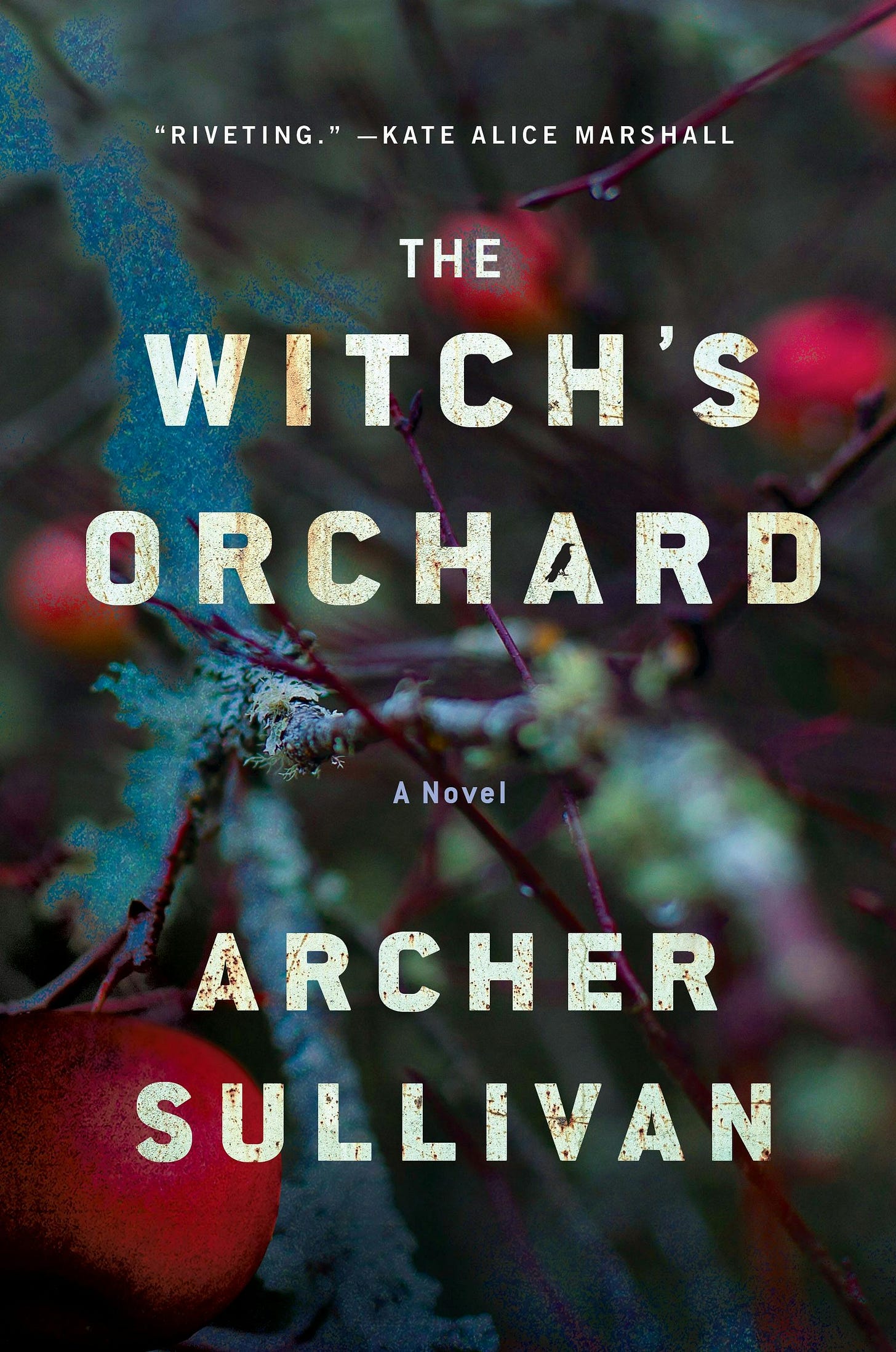

Archer’s debut novel, THE WITCH’S ORCHARD, is out now.

Obviously, Archer Sullivan had me at “Appalachian PI novel.”

THE WITCH’S ORCHARD, Archer’s debut novel, sends her Air Force special investigator-turned-PI Annie Gore into the hills of western North Carolina where, ten years earlier, three young girls went missing, and now the brother of one of the girls wants answers. Archer takes the familiar tropes of the PI novel—a stubborn and tenacious protagonist, a great car, a town full of secrets—and adds layers of Appalachian folklore that makes THE WITCH’S ORCHARD an atmospheric, almost gothic read. It’s one of the best PI debuts in years.

At the book’s heart is Annie Gore—smart, complicated, wary, dogged. She’s a fantastic protagonist, and I suspect she and my own Henry Malone would get along. I’m looking forward to more Annie books for years to come.

Archer’s lived everywhere from Monticello, Kentucky to Manhattan, New York, and from Black Mountain, North Carolina to Beverly Hills, California. Her work has appeared in Ellery Queen Mystery Magazine, Tough, Shotgun Honey, Reckon Review, and Rock and a Hard Place Magazine.

She’s also our next Five for Them, One for Me.

Let’s go.

FIVE FOR THEM

1. What was the origin point for your novel THE WITCH’S ORCHARD?

As with every writer, the book is a product of the sum of my personal life experience (growing up and moving around Appalachia, moving away) and all the stuff I read and watched and loved (Sherlock Holmes, The X-Files, Star Trek, Masterpiece Mystery) and that is all true.

But it’s also true that one afternoon, I was sitting around playing a video game (sadly I’m not sure which one now but possibly Outer Wilds?) and the details of a scene suddenly popped into my mind: a farm house, the hot, summer sun through an open window, white curtain billowing, an empty living room where the TV is still running a movie that no one is watching, a piano playing somewhere else in the house, and on the couch, an apple-head doll which has taken the place of a little girl. That was the moment that sparked the book. It was a scene I couldn’t let go of until I’d found the right place to put it. Ultimately, that place was the background for the events in The Witch’s Orchard.

2. This is a first novel, but you have a strong short story background. What was it like transitioning from short stories to a novel?

I do love a short story. Most of my mine are written in one or two days and then I go back and forth with revision here and there and then it’s done! By contrast, I spend months planning and then writing a novel and then months more on revision. Stories are so much faster! But writing a novel, weaving all those threads together, and spending time with the characters…I love the process, the slow building. And, it’s incredibly rewarding on the rare occasion when it actually works and everything finally clicks together and it all resonates and you write The end. (Of course, I only feel that way for a few minutes. Then revision anxiety sets in.)

3. You’ve talked about the PI writers who influenced you—everyone from Sue Grafton to Robert B. Parker to P.D. James—but were there regional/Appalachian writers outside the genre you drew inspiration from?

As a kid, my tastes veered more toward fantasy and sci-fi, plus classic British crime fiction. As an adult, I tended to reach more and more for PI (Robert Parker, Sue Grafton, Rex Stout) or thoughtful, atmospheric, mostly British crime novels (P.D. James, Ann Cleeves, and I know Agatha Christie is generally not thought of as an atmospheric writer but And Then There Were None is horrifying in its cheerful bleakness).

I will say that, as a child, I took my mom’s copy of Bastard Out of Carolina off the shelf and—reading Dorothy Allison’s masterful work at about eleven years old—it left a permanent mark on me.

4. We’re part of an extremely small niche of writers writing Appalachian PI novels; in fact, we might be the only ones. What were the challenges you faced translating the PI story to rural Appalachia?

Private investigators traditionally work in cities, and for good reason. There’s enough crime, enough good guys and bad guys, and—importantly—enough strangers in cities. Cities provide anonymity which provides potentially infinite cases. A PI’s job is to find shit out which, if they’re operating in a big city—within a web of people whose identities and activities are unknown to one another—is a tough obstacle for a protagonist, which is what we, as writers, want.

What I did instead, because The Witch’s Orchard takes place in a small, Western North Carolina town where everyone knows at least a little about everyone else’s life and history and personal tragedy and dirty laundry, is make the private investigator the stranger instead. Annie Gore, my PI, shows up and pries into people’s scars and it’s no wonder they don’t want to talk to her and, again, that’s what writers want. Obstacles are what make stories happen.

The consequence of this, of course, is that whereas Spenser scarcely ever left Boston and Nero Wolfe almost never even left his house, if I get lucky enough to keep writing Annie Gore books in the model I’ve set up, she’ll always be a stranger. Which means, it’ll be a different town or at least a different community of people each time. Spenser’s Boston, Nero’s New York, Kinsey’s Santa Teresa, all felt real and alive and tangible. My challenge would be to do that every time, always inventing a new place for Annie to show up and bother people.

5. Your bio describes you as a ninth-generation Appalachian, but also states you’ve moved 37 (!) times. You know out there in the world there’s no shortage of Appalachian stereotypes. As you were writing, were there expectations or cliches about Appalachian culture you wanted to upend or dispel? And did all of those moves affect how you look at Appalachia?

My nomadic childhood absolutely shaped who I am as a person and as a writer. I may have grown up in Appalachia but it was all over Appalachia. I went to thirteen different schools before high school which meant that, like Annie, I was always a stranger. While I understood some of over-arching general rules of the region, each place was different, with new people, new rules, new stuff to learn as fast as possible. Still, I actually I never really thought too much about being from Appalachia until I moved out of it.

My first month in Southern California, I visited a doctor at UCLA’s famed medical center where it came up that I’d recently arrived from Kentucky. She immediately made jokes about how I couldn’t be from Kentucky because I was wearing shoes and could read. I was stunned. Over the years, living in both NYC and LA, my husband (also a native Kentuckian) and I have heard all kinds of stuff like this. People learn pretty quick that any badmouthing about our home region results in swift education.

With The Witch’s Orchard, I just wanted to show at least a version of the Appalachia I grew up in and I wanted to do right by the people there, the people I grew up with, the people I came from. It wasn’t until my mom (an extremely tough critic on this subject, let me tell you) gave me her approval that I finally relaxed a little bit.

ONE FOR ME

Settle it once and for all: What is the proper pronunciation of “Appalachia”?

Ha! I feel like I should write here about the value of linguistic and cultural diversity and how there’s room for all pronunciations and we shouldn’t be fighting amongst ourselves. But, what I should do and what I will do are different: It’s Apple-atcha.

BOUCHERCON ROUND-UP

This year marked my sixth Bouchercon (I still count the virtual event in 2021), and it might have been the best yet—full of wonderful panels, fantastic conversations, amazing food, and of course being in New Orleaans, one of the great cities of the world. Check out my Instagram for a chronicle of the oft-questionable choices I made throughout the week.

But if you had to ask me the high point of this year’s Bouchercon, it was the continued growth of diversity within the community. Friday night, Queer Crime Writers hosted an incredible Underrepresented Writers event. Saturday night’s Anthony Awards presentation saw diversity and representation in the winners. Best Cozy/Humorous winner Rob Osler challenged readers to make every fifth book they read a book by an underrepresented writer. Best First Novel winner K.T. Nguyen and Best Children’s/YA Novel winner Suja Sukumar each spoke about the importance of diversity and inclusion, and joined Best Paperback winner Tracy Clark in shouting out Crime Writers of Color. Best Short Story winner Curtis Ippolito delivered a stirring call for writers to stay strong against an increasingly oppressive government and to defend not only their own rights, but the rights of others.

There’s this attitude that we should tolerate the wretched behavior of a few because they’re old or arrogant or own a particular bookstore, and more and more it’s becoming clear this is bullshit. Dinosaurs think they see a shooting star when in fact it’s a meteor coming right for them.

The rest of us understand crime fiction is the story of justice, and as a community, we’ll stand up and defend those coming for a seat at this table, to tell their stories and to speak their truths.

That’s all we’ve got for now. Thanks for coming. See you next time, and hey, let’s be careful out there.

Great interview as always—and congrats to Archer!!

Great stuff as always. And I agree with you about Bouchercon. I had a great time and it was great chatting with you.